Welcome to Black Sheep, a spin-off publication of my serialized memoir. SMIRK. While SMIRK was a deep dive into my unusual personal and professional relationship with one unique white-collar fraudster— Martin Shkreli — Black Sheep takes a broader view and tells the stories of a wider range of business crimes and failures.

This publication will examine cultural themes and motives that contribute to lying, cheating, stealing, and related self-inflicted disasters; the impacts of those events; and the people who play starring roles in these dramas. I find these tales both cautionary and fascinating; I hope you will, too.

Anti-Tech Resistance

It was only a matter of time before the Luddites came for AI. Professors, it turns out, are leading the charge.

Fueled by a viral New York Magazine piece titled “Everyone Is Cheating Their Way Through College,” university faculty are raising moral panic over students outsourcing their assignments to ChatGPT. The implication is that the machines are to blame.

But here’s the thing: While robots might make the process easier, academic cheating is a human problem, not a tech one.

To illustrate my point: MIT just disavowed a widely publicized study on AI and productivity. The author, 26-year-old doctoral student Aidan Toner-Rodgers—now a former doctoral student, as MIT quietly noted—allegedly fabricated the data. All of it. He may have even made up the lab where the research supposedly took place, describing it in his paper only as an “R&D lab of a large U.S. firm.”

Though loud in its tech-related ambition, his alleged wrongdoing was strictly analog, not the fault of AI. The mendacity echoed another case from decades earlier, journalist Stephen Glass, who infamously faked whole articles for The New Republic. Toner-Rodgers purportedly relied on the same basic human quality that Glass did: our desire to believe impressive lies.

*****

If you were a journalism student in the early 2000s like I was, Glass needs no further introduction. He served as one of the most emblematic cautionary tales regarding journalistic ethics, or rather, an utter lack of them. His story was adapted into a critically acclaimed 2003 film, Shattered Glass, starring Hayden Christensen. Like my peers, I watched the movie and recoiled in fascination and horror.

Yes, there have been other notable examples of sham reporting in major publications — namely, Jayson Blair in the New York Times and Janet Cooke in the Washington Post — but their actions were at least somewhat understandable, if not forgivable. Both journalists, who were Black, rapidly ascended in highly competitive, mostly-white newsrooms, where they succumbed to intense pressure to prove themselves.

Because honest reporting often falls short of top editors’ larger-than-life expectations, these reporters took shortcuts. Blair made up interviews and plagiarized material in at least three dozen articles between 2002 and 2003. Cooke won a Pulitzer in 1981 for her piece about a child heroin addict, titled “Jimmy’s World.” However, her award was revoked after she confessed under scrutiny from her editors to inventing “Jimmy.” She was also found to have embellished her resume significantly by claiming, among other things, to speak fluent French. Then-Washington Post editor Ben Bradlee, a “Boston Brahmin” (AKA old-money white person) who learned French in childhood from governesses, discovered that lie by interrogating her himself.

By comparison, Glass was a fabulist in his own league. Having grown up with a pedigree that should have provided him with ample social capital and reporting knowhow — he came from a wealthy Chicago suburb, majored in politics at the University of Pennsylvania, and was editor of the student paper — he nonetheless turned to brazen fraud. Glass didn’t just make up sources and interviews; he concocted entire news events. When questioned by editors, he supplied fake notes, fake business numbers (connected to voicemail services), and fake websites. In many ways, the cover-up was more calculating and amoral than the crime.

Glass’s fakery spree came to a crashing halt in May 1998 after TNR published his piece, “Hack Heaven.” The cinematic, too-good-to-be-true article told the tale of a 15-year-old hacker who broke into a software company’s network. Instead of having him arrested, the company supposedly hired him to keep quiet, lavishing him with $250,000 in stock options, a high-end computer, a limo ride, and a trip to Disney World. Glass’s story included a scene of the boy shouting his demands to the company at a Bethesda, Maryland, conference, flanked by lawyers, executives, and PR representatives.

Although the article passed TNR’s fact-checking process, a Forbes Digital reporter, Adam Penenberg, tried to follow the story and quickly discovered it was a figment of Glass’s imagination. Peneberg found no record of the hacker, supposedly named “Ian Restil,”; the software firm, supposedly called “Jukt Micronics,”; or the convention that supposedly took place. At first, Penenberg found “Jukt Micronics” didn’t even have a website, although Glass eventually created a crude one as pressure mounted.

Spurred by Penenberg’s digging, TNR launched its own investigation, and Glass’s deception came unraveled as he made increasingly desperate attempts to “prove” his innocence by fabricating evidence. The magazine found he had faked or distorted material in 27 of 41 stories he had written for TNR. He was fired. Forbes Digital published an exposé: “Lies, damn lies, and fiction.”

******

Flash-forward to MIT in late November 2024. AI was rapidly overtaking public discourse with the US presidential election dropping out of the news cycle. The fear of robots taking over intellectual labor, taking jobs from broad swathes of the middle class, hovered like a dark cloud. Then, Toner-Rodgers, a 26-year-old economics PhD student at MIT, gave dimensions to those anxieties with perfectly calibrated research.

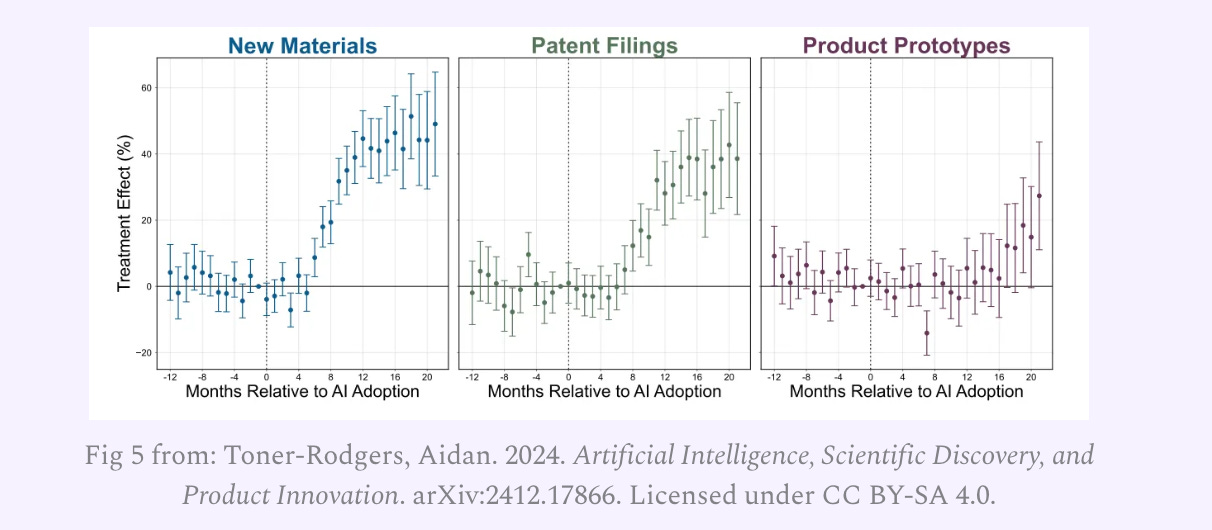

His paper, Artificial Intelligence, Scientific Discovery, and Product Innovation, which he self-published on a preprint academic site, arXiv.org, attracted significant attention. The study, as you can see from the title page below, supposedly focused on an R&D lab with over 1,000 scientists in a “large U.S. firm.” It found (again, supposedly) that AI-assisted researchers made 44% more discoveries, significantly increasing patent filings and product innovations.

More concerningly for knowledge workers, the study also allegedly found that only top scientists produced the increased output with AI (meaning research firms could potentially do more work with fewer people). The research also allegedly found that AI automated “idea generation,” leaving most scientists dissatisfied with their work because of “decreased creativity and skill underutilization.”

Hailed as a breakthrough in the understanding of AI’s potential impact on the labor market, the study was publicized in, among other places, the Wall Street Journal. On Dec. 29, 2024, WSJ published an article titled "Will AI Help or Hurt Workers? One 26-Year-Old Found an Unexpected Answer.” In the article, prominent economists Daron Acemoglu and David Autor, both from MIT, praised the study. Acemoglu described it as "fantastic," while Autor stated, "I was floored.” The Atlantic and Nature also put out feature stories on the research.

However, within two months, the all-too-perfect research paper came unraveled. A computer programmer reportedly approached Acemoglu and Autor about the study in January 2025, asking about the specific AI technology involved in the study and the lab where the experiment supposedly took place, which he had heard nothing about previously. Perhaps embarrassed by their inability to answer those basic questions, the two noted economists referred the matter to MIT’s disciplinary committee, which conducted a review.

On May 16, 2025, the university announced that it had"no confidence in the provenance, reliability, or validity of the data and has no confidence in the veracity of the research contained in the paper." The paper was taken down from arXiv (although the web-archived version remains available), and it was withdrawn from the Quarterly Journal of Economics, which had been reviewing the paper for formal publication. The WSJ briefly covered the study’s retraction.

Although MIT did not give details about the specific problems with the study or the misconduct at issue, citing confidentiality, one educated observer seized on the information and chronicled alleged signs of fraud in the research hidden in plain sight. On his Substack, The BS Detector, engineer and researcher Ben Shindel quickly posted a detailed breakdown of every red flag in Toner-Rogers’ results.

Those included the following:

The data source, a large R&D lab, was implausible. Shindel wrote: "Why would a large company like this take such pains to run a randomized trial on its own employees, tracking a number of metrics of their performance, only to anonymously give this data to a single researcher from MIT—a first year PhD student, mind you—rather than publishing the findings themselves?"

The results were too clean, too neat, and too contrived-looking. Most scientific results have at least some ambiguity or signs that they might not be statistically significant. Toner-Rodgers graphs and charts stuck to definitive, too-perfect patterns.

While not a smoking gun per se, the analysis he incorporated was also highly sophisticated for a first-year economics Ph.D., Shindel noted. He wrote: “It boggles the mind that a random economics student at MIT would be able to easily (and without providing any further details), perform the highly sophisticated technique from the paper he cites…especially in this elegantly formalized manner without any domain expertise in computational materials research.”

The scientific concepts in the research were also oversimplified to a point that may have appealed to laypeople and journalists, but would “probably drive a materials scientist insane,” Shindel wrote.

But perhaps most suspicious of all, an internet sleuth discovered (and Shindel reposted) a World Intellectual Property Organization panel decision against Toner-Rodgers over his registration of a domain that was “confusingly similar” to a major company’s trademark. The company, which filed its complaint Jan. 31, 2025, was materials firm Corning Inc. Toner-Rodgers’ offending website was “corningresearch.com.” The WIPO panel ordered that “the disputed domain name be transferred to the Complainant.”

Another tech industry observer, Mushtaq Bilal, the co-founder of an AI-powered tool for researchers, posted a tweet thread chronicling the Toner-Rodgers debacle and Shindel’s takedown. In one of his tweets, Bilal commented: “It reminds me of Stephen Glass, a journalist at The New Republic, who would cook up fake quotes and sources for his articles.”

*****

The Toner-Rodgers case reveals what institutions are still reluctant to say out loud: that cheating, whether by undergrads outsourcing term papers to ChatGPT or PhD students fabricating research, isn’t a tech problem. It’s a reward problem. Our prestige economy demands polish, confidence, and results that align with a mainstream narrative. So people—students, researchers, journalists—deliver what the system wants.

Aidan Toner-Rodgers responded to the same incentives currently nudging students to ask large language models for thesis statements. The only difference was scale. Like Stephen Glass decades before, Toner-Rodgers allegedly followed a familiar script: game the details, simulate insight, and give people what they want to believe. And it worked until someone asked follow-up questions.

So when professors shake their fists at students for letting AI do their thinking, they might want to ask what kind of thinking the system actually rewards. Robots didn’t cause academic integrity to collapse. They just illuminated the cracks that were already there.

Thanks for taking a look at Black Sheep! For further reading from my serialized memoir, SMIRK, that echoes the themes from this piece, please check out the following:

Chapter 5, Part 3: The Horatio Alger myth

Chapter 14, Part 3: "No Shortcuts"

Chapter 6, Part 4: What’s in a scam?

See the full table of contents for SMIRK here. 0

Paid subscription is required for full access to SMIRK and the Black Sheep archives.