Chapter 13, Part 5: Michael Bloomberg

Despite his praise of Trump, Martin Shkreli didn’t vote for the real estate mogul in the 2016 presidential election. But in 2020, he might have voted for Bloomberg if he could.

What does the world look like through the eyes of a self-made billionaire, I wonder. Maybe they believe, as Egyptian pharaohs did, that they are literal Gods — that humanity exists only to further their ambitions, and that everything they touch, whether it’s a business plan or a wad of toilet paper, is improved by the encounter. Maybe they feel extremely validated for all of their life choices. Every whim that tickles them must Signify Something Important. Every opinion their neurons generate must be an Incontrovertible Truth.

Or, perhaps like the rest of us, they’re driven by ordinary human emotions and flaws like pride, vanity, insecurity and a yearning for attention, love and satisfaction. It just might take much more substantial, dramatic, and expensive acts to silence their inner critics and feel accomplished — whether it’s buying a superyacht with a private submarine and rooms covered in stingray leather, taking over a social media platform, or running for president of the United States. Like us, they’re running a rat race. They’re just after a much, much bigger block of cheese.

Ego was probably the impetus behind Donald Trump’s run for president in 2016. Political analysts speculated that he hadn’t even been contemplating such a move – at least not seriously, as more than a publicity stunt – until then-President Barack Obama roasted him at the 2011 White House Correspondents’ Dinner. Comedian Seth Meyers, the host of the event, further called Trump’s rumored political interests “a joke.”

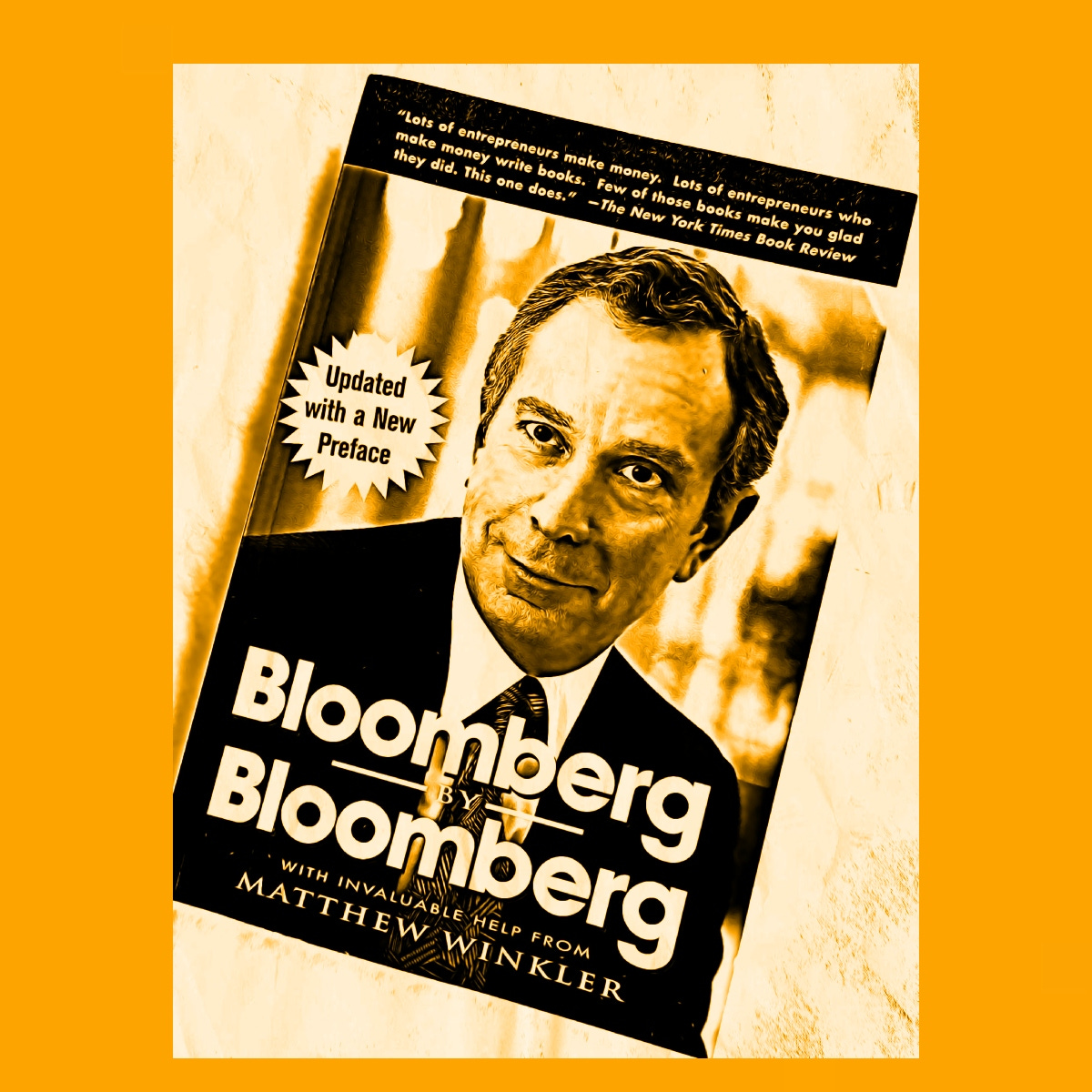

Not to be outdone by Trump, more a cartoonish caricature of a tycoon than a real one, an astute, competent and respected self-made New York billionaire stepped up to the plate in 2019: Michael Bloomberg. Maybe his operating assumption was that the only thing that stops a “bad” guy with a multi-billion dollar fortune in a battle for the free world is a “good” guy with a larger multi-billion dollar fortune. (Forbes currently estimates Trump’s worth at $2.5 billion and Bloomberg’s at $94.5 billion.)

In any event, it was possible that Bloomberg could have lured away the “pro-business” votes from Trump. I know he had at least one very devoted, well-known fan who had previously loudly supported Trump but would have happily stumped for the “good” billionaire instead (that is, if he weren’t locked up in prison at the time and viewed as an “untouchable” pariah by the entire political establishment): “Pharma Bro” Martin Shkreli.

While Martin Shkreli publicly proclaimed adoration of Trump in 2016, and even played part of the famous single-copy $2 million Wu-Tang Clan album over a live stream in celebration of Trump’s victory, he didn’t actually vote for the reality TV real estate mogul. Martin didn’t bother himself with voting in any election, presidential or otherwise. He despised politics and politicians in general. Had he been able to do so in 2020, however, he told me he might have made an exception for Bloomberg.

Like many young entrepreneurs and financiers, Martin idolized Bloomberg. He had, after all, achieved..