Journalists, television producers, and other observers have asked me many times, in the aftermath of my public relationship disaster with Martin Shkreli, how I managed to handle it all.

What steadied me as I navigated my way out of a marriage, and out of my career as a mainstream media reporter, into the arms of a famous white-collar criminal…and then under an unflattering media spotlight as he spurned me? What was my outlet through the ups and downs and eventual devastating conclusion? What was my “rock”?

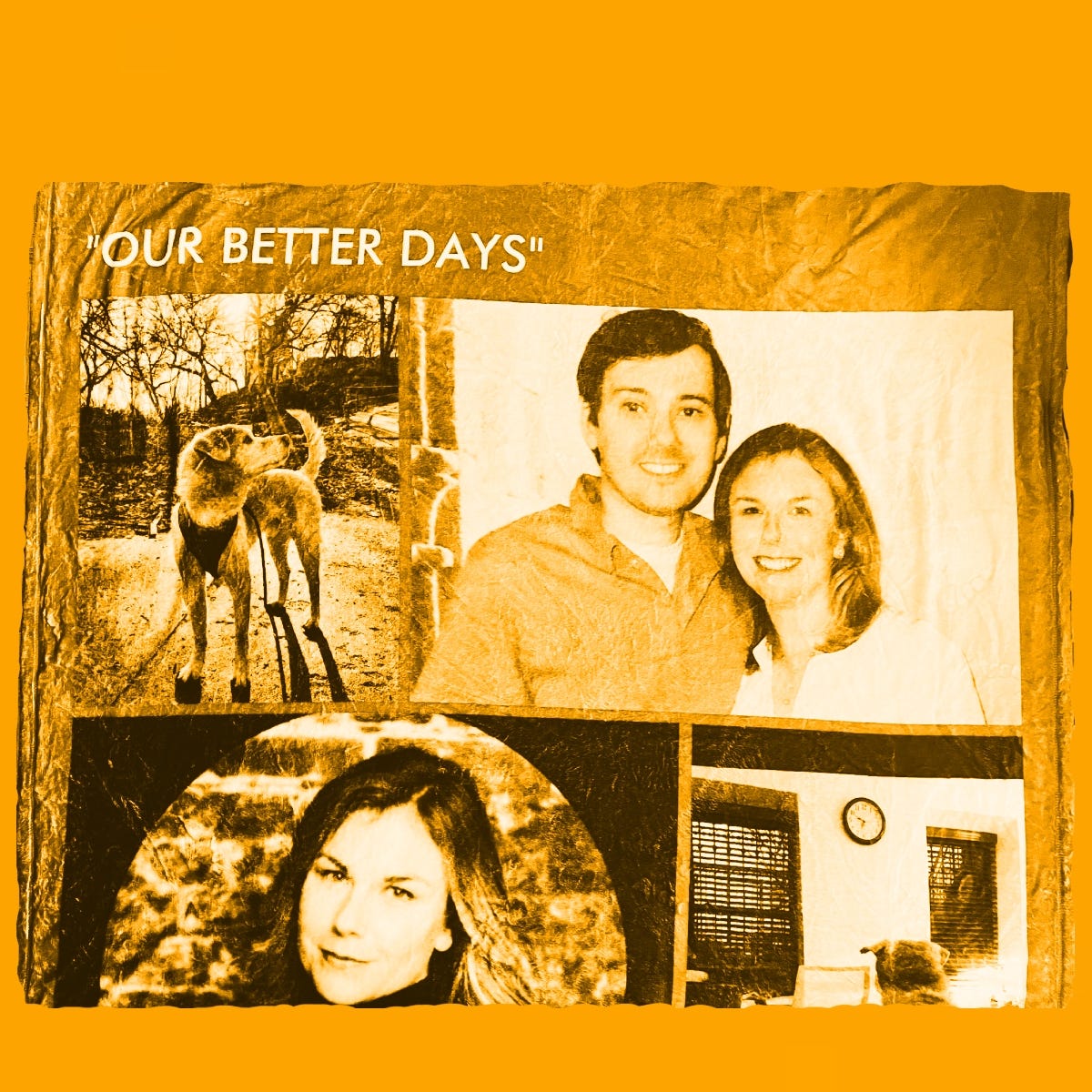

My usual answer was that I was blessed with supportive family and friends and that I had a high degree of self-reliance. Both of those things were true. But I was omitting one source of unconditional love which had done much to sustain me. He had been by my side since my early 20s, through more transformative experiences than I could count, including everything involving the “Pharma Bro.” He was my dog, Jack.

I did not realize how much psychic weight I had heaped onto that gangly, copper-colored, 23-pound canine, and how deeply he had burrowed himself into every aspect of my life, until he was gone. That day came just recently, on March 11, 2023. After 16 years with Jack, I cradled his furry form in my living room while he took his final breath. His heart thumped faintly one last time as I held my palm to his chest.

When the veterinarian who had euthanized him zipped him into a dog-sized body bag and carried him away, years of emotions that he had kept at bay rushed toward me like demons flying out of Pandora’s box. Fortunately, a good friend was with me to help me through the loss, but I still felt more alone than I ever had before in my life. The cheerful, brave face I was able to put on in interviews and in Twitter fights about Martin could not be summoned. Without Jack somewhere in the background, tip-tapping his way along the wood floor, I wasn’t invincible anymore.

Jack factored heavily as a character in nearly all of my adult relationships, including with my ex-husband and with Martin. Although Martin never met Jack, the dog still served as an always-safe conversation topic and a bridge through so many situations that might have otherwise alienated us from each other. Strangely, Martin and Jack also had remarkably similar personalities. “Lol, you definitely have a type, don’t you?” Martin said to me once, when I was expressing annoyance at my dog being difficult over something…