It’s funny how formative experiences tend to repeat themselves. Being hauled into a Bloomberg HR meeting over my tweets about Martin Shkreli in 2018 didn’t feel that unfamiliar. A template for what the discussion was all about, what would likely be said and unsaid, and how management would try to “deal” with me was already imprinted in my mind — from way back when I was a freshman at St. Teresa’s Academy, an all-girls Catholic prep school in Kansas City, Missouri.

Chapter 8, Part 2: Catholic School Girl

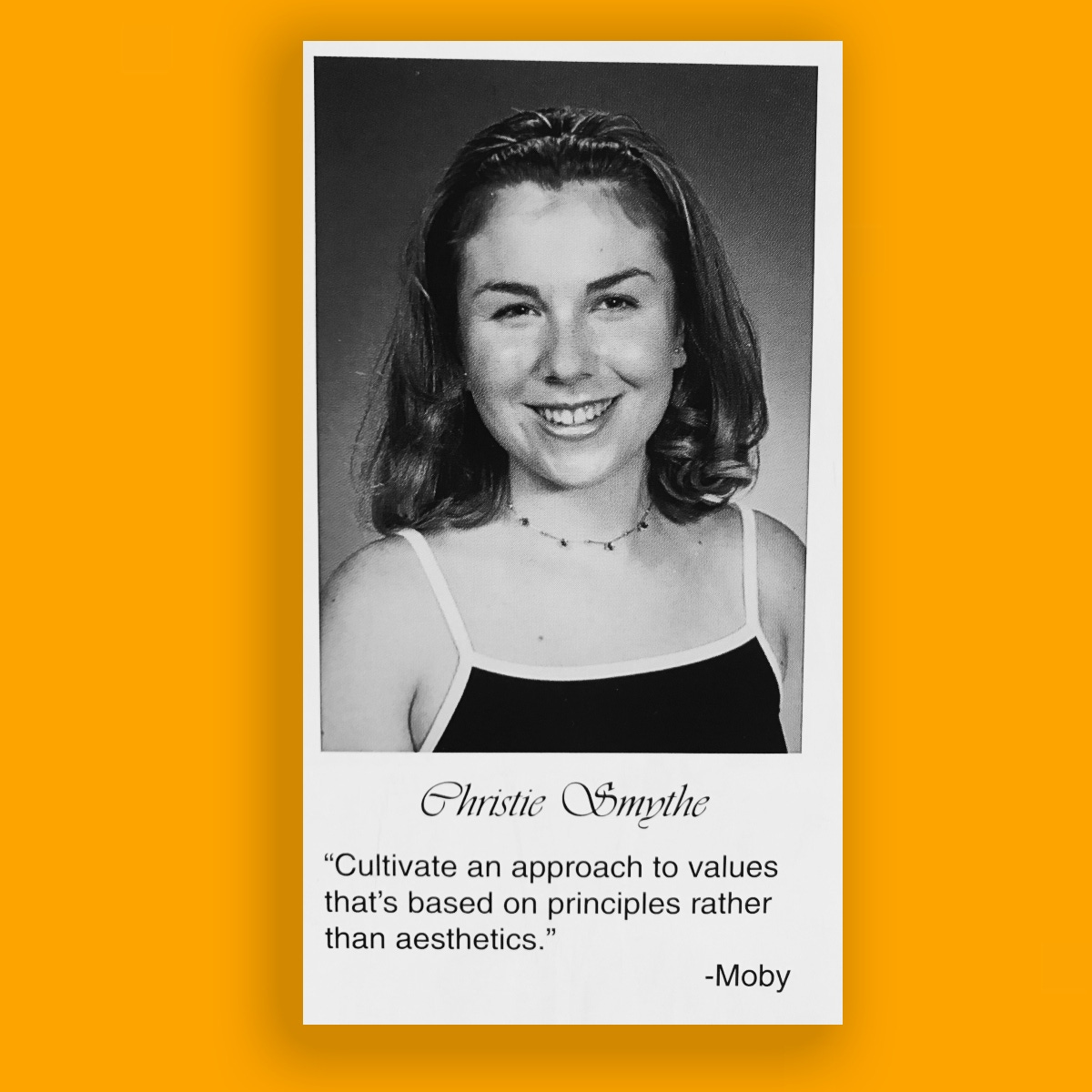

I learned an important lesson about how institutions prioritize their public image back when I was in high school.

Oct 17, 2022

∙ Paid