For the most part, there was nothing complicated about Martin Shkreli’s feelings for “the media.” Like many people caught in a public shitstorm of their own making, he enthusiastically blamed the Fourth Estate for all of his woes. During his talk at Princeton in April 2017, he correctly identified a young woman who asked him a question as a student reporter. Instead of answering her, he declared, drawing a roar of laughter and applause: “You should know that I hate…the media.”

But in the same breath, he made a tiny carve-out for me. I was sitting in the audience. He said that he had “made friends” with one “honest reporter.” “She’s here now,” he said quickly, through a sheepish grin.

Though we were friends then, and grew to be much more just a year or so later, he never really reconciled how much he despised the press, as a general rule, and how much he came to care about me. No matter how philosophically aligned we were — I agreed with some of his criticisms of the media, like how it was incentivized to promote certain biases over critical thinking — he harbored a tiny sliver of mistrust. It would erupt from time to time like a pus-filled sore.

Part of him seemed to be waiting for me to turn on him and abuse his intimacy, much like the now-late New Yorker writer Janet Malcolm all but instructed reporters to do in The Journalist and the Murderer. When I went public about our relationship in ELLE in December 2020, against his wishes, I confirmed all of his worst suspicions. His terse, dismissive “best of luck in future endeavors” comment in the article contained those multitudes.

But I don’t think I was being coldly exploitative then — and I don’t think I am being that way now. Whatever happened between us, even if it was heavily influenced by highly unusual and intense circumstances, was just as much a part of his life as jacking up the price of a life-saving drug, being a jerk on the internet, lying to his investors, and everything else “negative” he was known for. The human side of him was part of a fuller, more honest picture. Whether he liked the idea or not, I thought maybe I had a role to play in showing it.

What it revealed was that Martin Shkreli — the “Pharma Bro,” the “sociopath,” the “narcissist,” the “jackass,” the “troll” — could love. He may have come to regret falling in love with a journalist, and may now try to downplay it or bat away any suggestions that he had real feelings for me. But both his actions and words from a few years ago spoke loudly to the contrary. To anyone directly observing, he was smitten.

Months before Martin and I said our first “I love yous,” his cellmate in the Brooklyn MDC, a Jamaican man incarcerated for drug offenses, already had an inkling he was sweet on me. “I thought y’all were bunny and Clyde,” he wrote to me recently, meaning “Bonnie,” obviously. But “every time I use to tell him that I know from how he sound about you he would [deny] it,” the former cellmate added.

“On one occasion I was playing with him telling that he [should] link me up with the reporter he's always talking about, ‘Christie,’ [which] meant you,” the cellmate wrote, meaning set us up for romantic purposes. Martin apparently “got so infuriated.”

“I was just playing with him telling him that she might need a bad bwoy [meaning ‘bad boy’],” the former cellmate wrote. “He was so tight. He try not to speak to me the whole day.”

Later on, when Martin and I were “dating,” so to speak, he didn’t just express love for me regularly, he meditated on it. He thought of me, for instance, while he was reading Oscar Wilde’s De Profundis, a lengthy letter the Victorian-era playwright penned to his former lover while in prison for homosexuality.

And whenever he had access to a contraband cell phone, he would text me that he loved me nearly every day. He would call me “babe” and “boo” and “Honeybear,” a pet name we adopted for each other, which referenced the plastic containers used in FCI Fort Dix for contraband alcohol. And he would engage in all sorts of playful and serious banter about our anticipated future together.

When people on the internet later mockingly (or wishfully) assumed he didn’t care about me, based on his single angry remark to ELLE, I could only laugh, dumbfounded, to myself. There was just so much evidence that proved otherwise.

One of the biggest challenges I faced to writing this piece was having to go through all of that evidence. Along with stirring distracting nostalgia, the task was really time-consuming. I have literally hundreds of prison emails and illicit WhatsApp messages from Martin (where he often used a pseudonym “Dan Irving”) squirreled away on at least four different computers, external hard drives, cloud drives and elsewhere. Not all of them obviously are love notes or conversations about “us.” But a substantial fraction are.

From the very beginning, Martin showed a tremendous capacity for almost childlike affection. After we first revealed our feelings for each other, amid the smells of microwave food in the FCI Fort Dix visiting room, he asked me, with shining eyes, if he could call me his “girlfriend.” I answered ambiguously. I wasn’t quite ready for that, but I assured him my affection was sound. Eventually, I did let him call me his “girlfriend,” “S.O.” (for “significant other”), and experimentally, his “wifey,” among other endearing titles.

In our daily WhatsApp chats, we would talk about our similar quirks and foibles — we were both very clumsy and absent-minded — and make jokes about how “when” we lived together someday we’d have to make sure to order wine glasses by the case and keep numerous phone chargers around the house. (Because we’d break too many of the former, and lose too many of the latter.)

Although he was never comfortable with the idea of sharing our relationship publicly, he wasted little time telling people he was close to how he felt about me. He explained the situation to his parents over Facetime on his contraband phone, and told one of his defense lawyers, Marc Agnifilo, about us. Martin’s dad and lawyer were both immediately supportive. Agnifilo, being a sharp observer of human behavior, was apparently completely unsurprised by the news that we were an “item.” And Pashko Shkreli suggested we have a prison wedding.

Interestingly, there is very little in our hundreds of messages that is explicitly sexual. (Martin may have relied on his extensive list of “side chicks” for satisfaction in that regard.) If anything, I talked more about sex than he did. But there were a few comments from him, here and there, that were deeply suggestive. He told me that once, for instance, he woke up his bunkmates in Fort Dix by shouting out my name in his sleep. (He sleep talks, apparently.)

”That’s sweet,” I told him.

”It’s…something,” he replied, declining to elaborate further.

More often, we talked about buying a townhouse in New York together; about what our wedding would be like (a beach wedding in San Diego, perhaps?); and about raising our future kids. We assumed, based on our own characteristics, that they would be smart, restless, and have problems with authority. We planned to start them out in public school, for socialization, and let them choose to construct an independent learning plan for themselves, if they seemed ready for it, in their early teens.

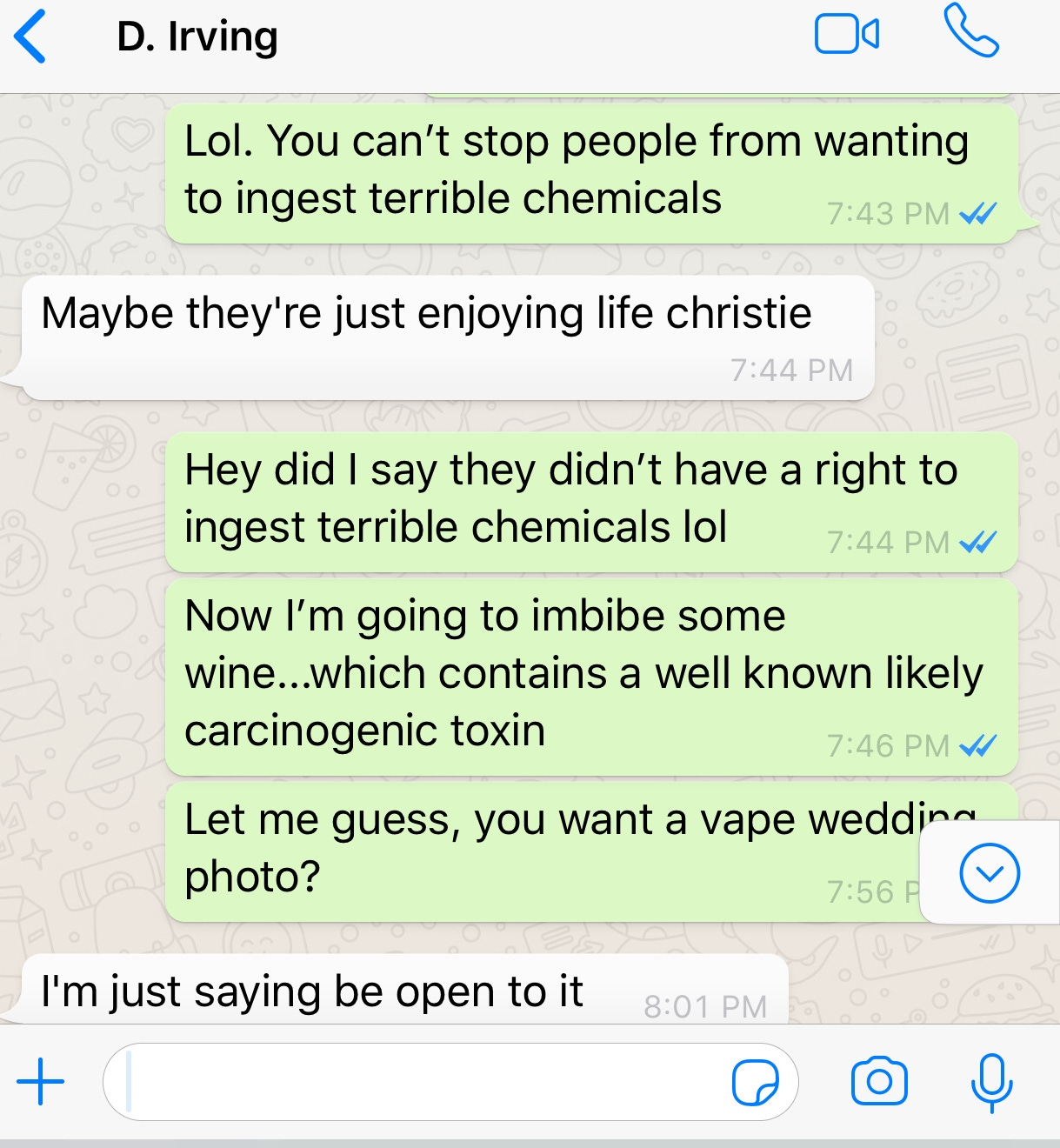

Once, we bickered about the popularity of vaping, which led me to joke: “Let me guess, you want a vape wedding photo?” He replied, playfully: “I’m just saying be open to it”.

It nagged me a little that he couldn’t seem to let go of his flirtations with other women. The Shkreli mind, I realized, was always developing a Plan B, C, and D if Plan A didn’t work out. I assumed he kept the “side chicks” partly for that reason. He was also upfront with me about his dalliances, and would proactively assert that he intended to get help from a psychologist and “work on” that problem. It seemed somewhat reassuring to me that he knew he had “issues” and wanted to address them. I wasn’t a jealous person, and I believed honesty and respect were much more important to relationships than pure monogamy.

When I was visiting him once, I explained to him that I completely accepted the possibility that he might decide to go off and “party with strippers in the Hamptons” or indulge in other wild temptations when he got out of prison. He had the option, after all. He received dozens and dozens of letters from admirers. He assured me, forcefully, that was not what he wanted. He wanted a life with me, he insisted.

While our relationship could only be PG, maybe PG-13 at best, we were able to show some physical affection for each other at times. FCI Fort Dix, staffed mostly by former military people, was notoriously lax about rule enforcement. Contraband, including drugs and cell phones, flowed with ease into the building. And in the visitor room, inmates and their “guests” could get relatively cozy by scooting chairs close together, interlacing their legs, holding hands, and even stealing extra kisses now and then. (Some people, of course, pushed boundaries and took a lot more liberties.)

Martin and I held hands often for hours. He would sometimes throw his head downward and kiss my hands when he was feeling particularly enamored. He would stretch one arm out casually, and graze my ankle with his fingertips. Our goodbye kisses could be downright passionate, and he would occasionally slide his hands along my backside. “I love every part of you,” he told me, matter-of-factly. “And if I didn’t, you’d know it — because I’m an asshole.” I laughed.

A fan of indie and emo music, he would sometimes propose unusual or semi-obscure suggestions for what “our song” might be…if we got married. He liked Regina Spektor’s “Samson,” for instance. The lyrics, which reference the Biblical Samson and Delilah, were a little too “on the nose,” I protested. (It begins with the words: “You are my sweetest downfall.”)

The last time I saw him in person in prison, in February 2020 at Allenwood in Pennsylvania, he offered another suggestion. He emailed me immediately after my visit. The subject line was simply “The Queen.”

It was a song by one of his favorite “post-hardcore” “screamo” bands Pianos Became the Teeth. “Maybe it can be ‘our song,’” he wrote. “The Queen = you.”

I listened to it, having a hard time imagining using the deconstructed, discordant melody as a wedding ballad. But the words were sweetly touching and very evocative of “us” — whatever it was we were to each other.

And my dirty hair in your lap will be the feathers in the grass

But for now your sugar the sap in my selfish glass

You want to be planted beneath the leaves

Bloom and blow with the breeze

But not yet, but now now

We can always be found